All day baking. At work I regretted wearing tight jeans. Flour fireworked on everything. I was tired, sluggish. Cherries boiling in pink liquid, cake batter smoothed across a sheet tray. “When I cook, I am also researching the relationship between the body and language, between self and other; I am learning how to think against a rationalist and patriarchal history of knowledge,” writes Rebecca May Johnson. How to describe these monotonies, the repetitions that make my wrist know the angle with which to hold the bench scraper, leaning my weight into it to cut butter.

At home I assemble the cake I’m making Dylan for Valentine’s Day. I spread out across the length of the countertop, spilling all over the floor I just cleaned yesterday. Eating a dinner of leftover rice in big messy bites, I rise periodically from the table to check on the sugar heating up for caramel. Vaguely resentful toward him, though he doesn’t even know I’m doing this, didn’t ask for this gift in the first place—I do so much for you, I could be writing, etc. How these thoughts rise from my subconscious, the histories they trace. The compulsion of domestic labor, or the impulse to conflate it with love.

“They say it is love,” writes Silvia Federici in Wages Against Housework, “they” a menacing, structural force and also the person, people, with whom you live, whom you do love. Federici writes that housework is not considered labor—and so not compensated as such—largely because it is presumed to be closely affiliated with feminine instinct and care. “Capital had to convince us that it is a natural, unavoidable and even fulfilling activity to make us accept our unwaged work.”

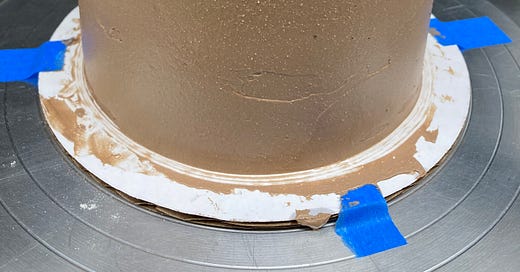

For Valentine’s Day I am making Dylan a triple-layer vanilla cake with grapefruit curd and caramel buttercream. The grapefruit curd is not quite tart enough, and I had to improvise cake pans with aluminum foil, so the layers are a bit crooked. I was thinking about the difference between baking for strangers and baking for the opposite of a stranger, whether the act itself is changed, whether love really does factor into the steps of a recipe.

Certainly the conditions have been altered. I took off my tight jeans the second I stepped inside, threw them in the hamper. I lit candles, turned on the lamps and the string lights. I texted Clare and scrolled through images on my phone, the horrific ongoing slaughter of Palestinians, a child’s torn-apart body draped across the jagged edges of a building made rubble, and meanwhile the big football game: confetti, gold pants.

I began writing while the caramel cooled, and felt a sparking, a momentum there in my home surrounded by my books and the growing mess on the countertop. I liked vacillating between my laptop and the kitchen, allowing for these interruptions to punctuate each activity with such regularity that they began to meld together. It was different from the kitchen at work, which runs on efficiency and breathlessness—here I could be scattered and unfocused, timeless and expansive.

But the work is the same, I thought as I piped a ring of buttercream around the edges of a cake layer. The materials the same—the texture of the grapefruit curd so familiar to me, though at work we make it with lime. What is the value of this work, and does that value change when the result is a marketable product rather than a gift? Johnson: “The continued status of domestic work as barely-work or unskilled work is reflected in the fact that cooking and cleaning and caring are among the most poorly paid and precarious forms of labor in capitalist societies.”

Virginia Woolf in Three Guineas, describes a woman’s place in society as “between the devil and the deep sea”—between the entrapment of domestic servitude and the toxicity of the professional market. Johnson writes that she stands in the kitchen “between Martha Rosler and Nigella Lawson;” the difference between Rosler’s short film, Semiotics of the Kitchen, a depiction of female erasure and objecthood in the kitchen and Lawson’s insistence on the pleasures of the kitchen. Baking cakes as paid labor and baking cakes as labor of love.

Virginia Woolf writes of her duty as a writer and a woman to kill the “Angel in the House”—the housewifely figure who performs her domestic obligations with grace and good-nature. She writes that she’s been able to accomplish this: “She died. But … telling the truth about my own experiences as a body, I do not think I solved.” The Angel no longer exists in her—but what to do with the body that remains?

I washed the dishes when I finished decorating Dylan’s cake with pink tic-tacs. I wiped down the countertops and put the mixer back in its place on the shelf. Leaning down, my back hurt. The body’s firm presence, its weird illegibility—how to allow it to exist in the kitchen and in the office, in the bedroom and on the street—contradictorily, clumsily, consumingly. And, too, as Woolf writes, to tell about it—to let language occupy these spaces also, alongside the body. “I am writing against the tendency for people to diminish cooking as almost the opposite of thought,” writes Johnson. I am cooking against this too.

If that's the cake you made, whatever thinking you were doing came out as energy in the cake and another thoughtful, provocative piece. Maybe baking or cooking can be divorced from the obligations, the social expectations, and the demands to just enjoy the creative act and the ability to express oneself in a different way. Easier said that done I suppose.