What I want to say is something about beauty. How to live as a person who is looked at, a woman. How to hear one’s beauty spoken of; how to hear nothing, silence. How to maintain a sense of one’s own beauty as that beauty festers, or else, how to abandon beauty as a pressing concern. How beauty changes, mutates, bends. How to live as a person who is looked at. It’s just I’m not quite sure how.

John Berger in his 1972 BBC series: “Men dream of women; women dream of themselves being dreamt of. Men look at women; women watch themselves being looked at.”

I have gained weight; my skin is tired, uneven; my shoulders hunch awkwardly. I keep trying to tell myself that conventional standards of beauty are sexist, racist, boring on top of it all, etc., but it is difficult to translate this logic into the irrational grammar of feeling and desire, sharpened, solidified by a lifetime of being a woman in the world.

“Knowing that her life prospects may depend on how she is seen, a woman learns to appraise herself first,” writes Sandra Lee Bartky in Femininity and Domination. A woman is both “seer and seen, appraiser and the thing appraised.”

How childish I feel writing about tiny waists and clear skin—I should have grown out of this by now or my intellectual interests should have rendered these petty concerns irrelevant.

Wiping down a table the other night while staring at a beautiful woman eating fried chicken across the patio, wishing I had her tiny waist, clear skin, wishing I were smart enough not to, I thought, but isn’t it a bit naïve to act as though beauty is inconsequential?

The implication that these insecurities should have dissipated by now, a few years into the body positivity movement, despite the real, largely unchanged, material conditions of a world that continues to value women based on their proximity to a Eurocentric ideal of physical beauty. “The world [is] cruel for placing such an emphasis on something most of us ha[ve] no control over and, on top of that, calling us vain for caring,” writes Haley Nahman.

How to talk of this particular vanity. Understanding the insignificance of this concern, made more irrelevant by my own relative luck—white, thin, blonde, and nonetheless obsessing, the body graceless and mundane, wrong-angled and aging. For days I can think of nothing but the way my stomach feels pressed against my belt. I do not eat fried chicken, I eat a banana, a spoonful of peanut butter and try to fall asleep before I can realize how hungry I am.

*

I recently followed this account on Twitter that exclusively posts Agnes Martin paintings. They show up sporadically on my feed—precision interrupting the chaos, a brief puncturing quiet. I love the titles: “Night Sea,” “Drift of Summer,” “I Love the Whole World.”

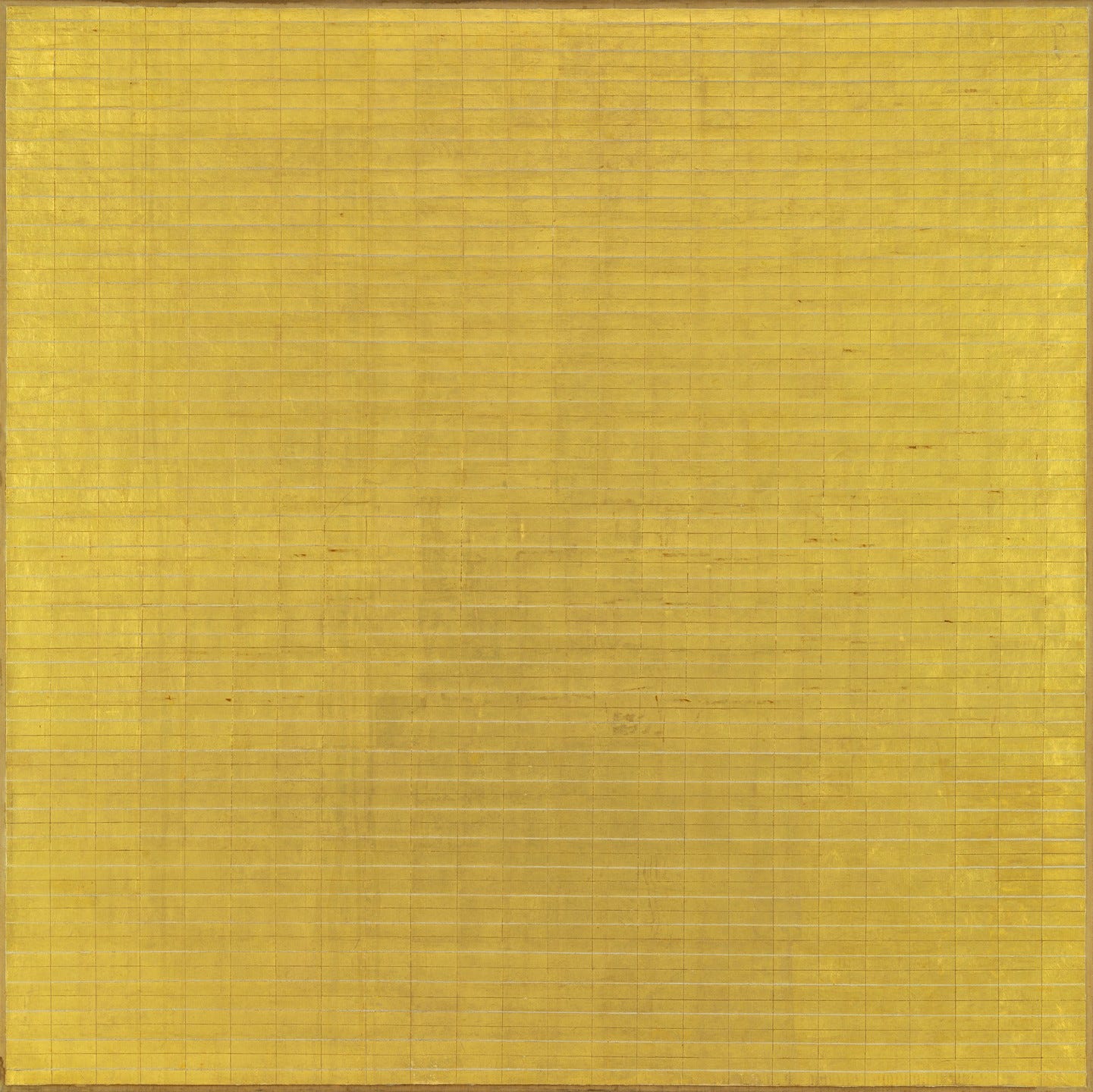

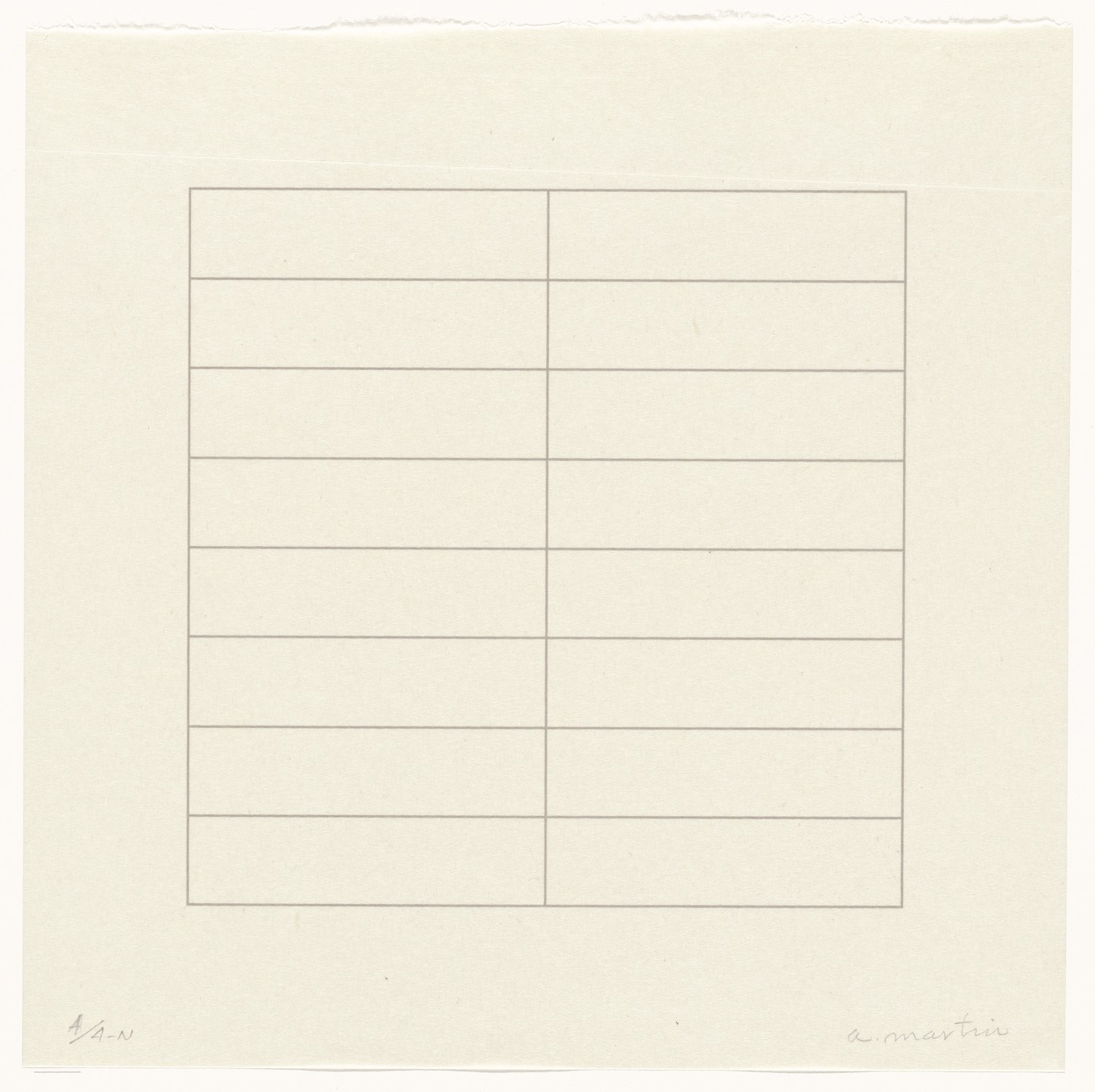

Martin is best known for her minimalistic abstractions, grids etched into large canvases, subtly textured straight lines. “Drops,” with its pin-like shapes so disparate from the sloppy anarchy of weather and yet evocative of its feeling nonetheless. Olivia Laing writes in The Guardian that Martin was interested less in the world itself than she was in “the abstract glories of being: joy, beauty, innocence; happiness itself.”

“I paint with my back to the world,” Martin said. My own appetites primarily material, physical, of the world, this world—oranges in the fruit bowl, friends, hands growing cold holding plastic cups of ice, a woman’s red hat against a darkening sky—my sudden interest in Martin seems to contradict whatever ethos I’ve constructed for myself.

*

My first week in New York, I took the train into the city, wandered until I had to pee. It was hot, humid, I wore tank tops and shorts those long days and watched men watch me crossing the street. I sat on a bench in Central Park and bought a ticket to the Museum of Modern Art where I used the bathroom and wandered slowly in my mask through the quiet halls and rooms, dead ends covered in placards.

I took a photo of Martin’s “Friendship,” a gold canvas, a grid whose lines vibrated with the futile attempt at perfection. I thought of Larissa Pham’s essay collection, which I had recently finished, how she describes the transformation of Martin’s work depending on one’s proximity to it: “if you stand back you see one thing and if you get close you see another, and all it takes is leaning forward to fall into the details of how it’s made and what it says.”

I stood at a distance, the six-foot square graspable in its entirety, glowing warmly through each precise rectangle. How stark the contrast between the white museum walls and the luminescence of that gold, lights pooled on the canvas. And up close the slight stuttering of the lines, the gold leaf torn, streaks of red, gradations, smudges. A zoomed-out precision made up of crooked attempts.

Looking at an Agnes Martin piece seems to me somehow both full-bodied and disembodying—the body overtaken by feeling, the body feeling. “The effect of Martin’s art is not an exercise in overarching style,” Peter Schjeldahl writes in The New Yorker, “but a mode of moment-to-moment being.”

*

I am trying to devise a way of saying this that makes me intelligent, thoughtful, a means of disguising vanity, insecurity, obsession as compelling formal inquiry. A way for this not to sound so stupid.

I am white, cis, able-bodied. I am tall and blonde and people have called me beautiful my whole life and I notice when they don’t. It is not interesting, these concerns, this sloppy line of self-indulgent half-analysis. Perhaps there are some obsessions that do not belong on the page.

But I can’t help but fascinate myself with that which I cannot surrender. My mealtimes erratic working nights at the restaurant; I eat a salad at 11pm and wake up in the middle of the night starving, sharp pain in my stomach, heart racing. I cannot feel full; I cannot stop feeling my jeans tight against my thighs, pressing textured seams into my skin.

A few weeks ago, reading bits and pieces of Brian Dillon’s The Hypochondriacs at the library (my first time there, masked and tiptoeing to avoid my feet squeaking against my shoes, some kind of construction making distant noise in the corridor), I noted Dillon’s association of hypochondria with eating disorders, their similarities: “obsession, withdrawal, repetition, a refusal to accept ‘rational’ answers to the perceived predicament.”

It’s easy to call anything beautiful; the chipped vase I picked up on the sidewalk, the dog hair on the couch, the masked woman in the grocery store testing mangoes for ripeness. The unbeautiful, the near-beautiful becomes a more complex beauty. The aesthetic ideal versus the narrative arc of beauty, the latter of which holds depth, richness. I know this.

I steal glances of myself in store windows and everything is wrong—knees, belly, my weird crooked walk. Annoyed by my body, my relentless vanity, I avoid my reflection for the rest of the day, imagine its odd angles appearing awkward nonetheless.

“From earliest childhood, she is taught and persuaded to survey herself continually,” says Berger.

*

Though such preoccupation with one’s physical appearance is supposedly narcissistic, beauty, or its opposite, is not without consequence. “The conditions under which we loathe ourselves are socially constructed, but in practical terms, they’re very real,” writes Amanda Mull in a 2018 Vox article.

“Fat people are turned away from help for serious medical issues because of their weight. Black people are more likely to be the targets of state violence. Trans people are murdered at a rate far outpacing the population average. Having certain types of bodies makes you more likely to die an early and unnecessarily painful death that will be blamed on you before your body is even cold, so I’m not sure why it’s so mystifying and dismaying to the world at large that people in those bodies might not think much of themselves.”

One of my favorite critics, Andrea Long Chu, echoes Mull’s interrogation of the body positivity movement in an interview in The Point Magazine, saying, “I cannot stand it. It is just anathema to me.” She continues to claim that body positivity suggests to the individual that the reason for their self-loathing derives from “a lack of having had my consciousness raised.” “No, my self-loathing is precious to me, and it is a form of knowledge about myself, and it’s also by its own very structure fundamentally incapable of being fixed through consciousness-raising because self-loathing is a form of consciousness.” The problem of my body a snag in the fabric; I pull at the thread and choose to keep pulling.

*

Yesterday in an H&M dressing room on the Upper East Side. Myself surrounded by myself. Stretch marks, sloppy tattoos, my bra strap slipping off my shoulder. These hours of thick silence—I’d spent the morning at the Guggenheim, alone, taking notes, a monologue of attempted art criticism stuttering on in my head. Until I felt not so much separate from my body but so far inside it I had to dig my way out. Meeting my gaze in the mirror, my brow furrowed every time; I watched myself turn in $35 jeans, held my stomach in, stood on tiptoe, looked up at myself surprised again by those eyes, ostensibly mine. I imagine myself a body moving through space—a perceived thing, watched, evaluated; a site upon which to lay one’s gaze—and yet I am so surprised to find myself here in the florescence and smudged walls—a body who is me who is moving through space, turning, turning, watching, thinking, turning.

*

In Berger’s BBC series, he speaks of the difference between nakedness and the nude figure: “To be naked is to be without disguise,” he says, patterned shirt, blue background. “To be on display is to have the surface of one’s own skin, the hairs of one’s own body turned into a disguise, a disguise which cannot be discarded.”

The disguise, the awareness of it (which may be at least somewhat invented; perhaps not everyone is watching me as I assume, or fear, they are—narcissism as self-consciousness)—a kind of paralysis, how trapped I feel in this visible body, the knowledge of its visibility.

As both the appraiser and appraised, one invents a kind of agency—that which is objectified becomes, also, subject. And yet, this alleged agency is self-referential, inhibited, narcissistic. Trapped in a cycle of interiority and insecurity, the body does not feel or act or respond to the external world itself, but rather to the world’s perception of it, the world always in relation to the self.

*

It’s a perfect day out there—leaves loose on all the trees, oranges, the blue blue sky. The clarity of fall, these certain colors. Met Halle in the city (thinking this morning about this pattern in our friendship—her in the city and I on the outskirts, crossing a body of water to gossip, sit in bars) where we drank coffee and wandered through midtown, shouting over traffic, construction. I went to MOMA and she turned back toward the Village. In my Danskos, I’m almost taller than her.

I was going to the museum just to see the Agnes Martin painting on the fourth floor—it seemed stupid, spending $25 to stand near a painting and write notes, but I wanted to be the kind of person who stands near a painting and writes notes, so I swiped my card at the ticket counter and climbed the stairs.

I always feel like crying in museums. Hallways, lighting, the muffled sounds of everyone among art. I was hungry though, and tired, and my feet hurt and I still had to work later. “Friendship” was situated as I remembered it—warm gold against white walls, hardwood. Tension in my neck and shoulders, I stood before it with my legs crossed. I wrote my notes: canvas under gold—gold looks torn; scratches, smudges; my body a shadow moving across the shine.

I did not stand there long, though I felt I should. There were no benches nearby and perhaps I was not so deep, so enraptured in the aesthetic experience as I was pretending to be. Looking through a window, I saw my reflection more clearly than it had appeared on the gold surface of Martin’s canvas. There I was among the high rises, sky. Ponytail slipping to the side, mask, bulky shoes. How long and lean I’d looked in the bathroom mirror a few minutes earlier—less so here, my skin transparent and leaking headlights of cars below.

I turned away from myself and made my way back to the stairwell, walking conspicuously fast among the lingering, measured revelers, toward the exit, toward the Subway, toward home. So I spent $25 to watch my reflection in a painting, then a window.

*

The body is not overtly apparent in Martin’s precise grids, curveless colors, and yet I find it there anyway. In an essay, Martin writes that all art is self-expression. “We must not think of self-expression as something we may do or something we may not do. Self-expression is inevitable.” Similarly, I think the body suggests its presence whether we invoke it or not—it is, for each of us, a singular site of feeling, both physical and emotional, internal and external; it is where we live.

Martin’s paintings, for me, capture the body in the throes of experience—the body looking outward, beyond itself. A freedom from the narcissistic duality of seer (of the self) and (the self) seen, a freedom of quiet, encompassing presence. Within, through, from the body. “There are moments for all of us in which the anchor is weighed,” writes Martin. “Moments in which we learn what it feels like to move freely not held back by pride and fear.”

*

“I was trying to experience the art as a feeling, rather than to think it through as a critic, which should have been easy, as I am not a critic,” is what I wrote in my notebook sometime last week after wandering the spiral ramp of the Guggenheim among Etel Adnan’s geometric renderings of the sun, sea, the Northern California mountain I too know well. I’m making all this up.

I left the MOMA this afternoon and walked the wrong way to the train; I had to turn around, pass the security guards again. All day I was trying to be a certain person, a person who walked among great art on a Wednesday morning, who thought interestingly, intelligent and irresistible in an orange coat. (Even writing this there is this humiliating hope that someone might offer validation—but you’re so beautiful!)

Sometimes it seems all writing is like this—a kind of posturing, a particularly told story. The narcissism of writing, of making anything, how desperate this desire to be seen, bare, but in a certain light. How what is an essential awareness of the reader can become, or perhaps inherently becomes, a self-conscious response to an outside gaze. The desire to be looked at—to be specific, intelligent, beautiful.

Then there I was wanting to leave the museum full of beautiful unconsidered canvases, all the art I abandoned for finding my way home through all the bodies. My own clumsy, lost, visible. Trying to find a sign for the 3 train, looking one way then the other.